Retired justices of the Supreme Court (SC) have been giving conflicting opinions on the issue of charter change (cha cha). Some say they’re all for it, while others say it is not needed at this time.

With the Marcos administration openly pushing for changes in some of the economic provisions of the 1987 Constitution, the likes of retired chief justice Hilario Davide and associate justice Antonio Carpio have expressed serious doubts on the need to amend the charter.

“Our problems are not due to the restrictive economic provisions of the Constitution,” Davide told lawmakers recently, adding that the problems “cannot be solved by removing its restrictive provisions and completely leaving to Congress the future under the clause ‘unless otherwise provided by law.’”

Davide also said that amending the economic provisions of the charter “would create more serious and disturbing problems and consequences.”

For his part, Carpio said there are ways to boost the economy without amending the Constitution.

In a recent press conference on cha cha, Carpio said the Philippines’ current investment laws already makes the Philippine economy liberalized.

It is, he said, more liberalized than China and Vietnam, both of which get more foreign direct investments than the Philippines.

The real problems are elsewhere, he said.

“The real causes are one, we have very high power rates, energy. Second, we have a very complicated bureaucratic procedure for investors, And third, rule of law,” said Carpio.

Almost all of the country’s problems can be addressed without altering or amending the Constitution, he said.

“The Constitution has nothing to do with the high unemployment here, with the low foreign direct investment, and with the slow growth of the economy,” according to Carpio, who is part of a broad coalition opposed to charter change.

On the other hand, retired associate justice Adolfo Azcuna – one of the original framers of the constitution, said the basic law of the land could stand some changes, given that the global situation today is different.

Another retired chief justice, Reynato Puno, has said that he favors an overhaul for the entire charter, arguing that “the world in the last decades of the 20th century is a totally different world in the opening decades of the 21st century.”

Just as there was a need to “update” the original 1936 Constitution in 1987, so too is there a need to amend that latest charter almost four decades after it was crafted, then approved by the people in a plebiscite, he said.

While not an SC justice, retired or otherwise, another framer of the 1987 Constitution, former Commission on Elections chairman Christian Monsod, said anybody gathered to amend the charter – be it via constitutional convention, constitutional assembly, or even people’s initiative – could be prone to abuse by corrupt officials.

It would “open the door wider with the insertion of that phrase ‘unless otherwise provided by law’ in the economic provisions,” he said.

“There is nothing special about them (pro cha cha lawmakers) that will address this so-called problem of restrictions against foreign direct investments,” said Monsod.

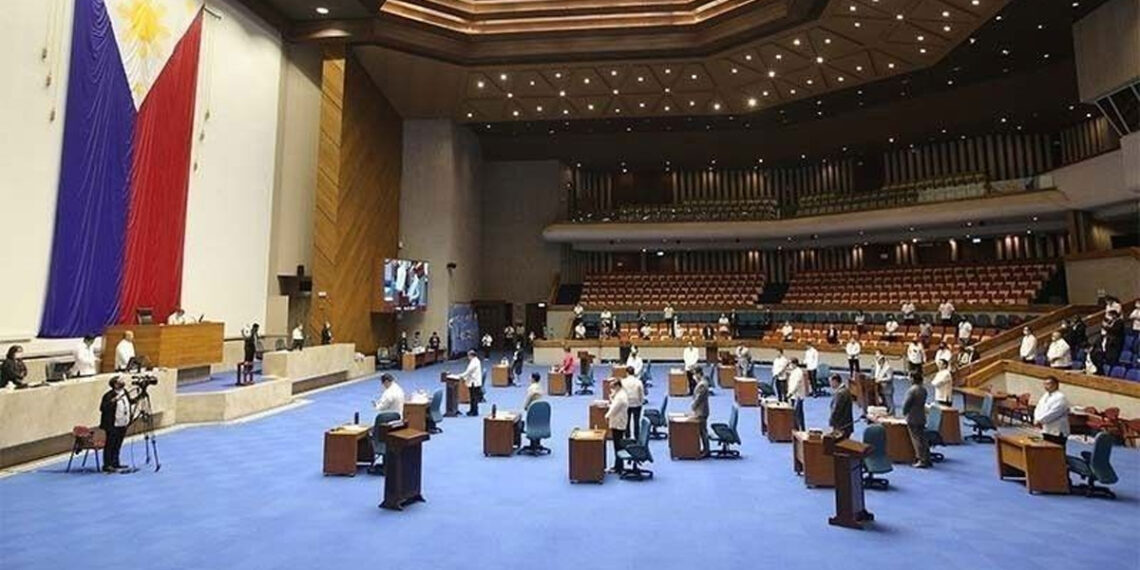

As of last week, it appeared that the majority of the 24 senators remain unconvinced on the need to amend the constitution. At least half have said that they remain opposed to the idea, which means the two-thirds vote needed from the upper chamber of the bicameral Congress to agree to amending the basic law is still out of reach.

This, despite the fact that Senate President Miguel Zubiri had a change of heart last month, when he started to speak in favor of cha cha after President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. met with him.