One of the major political discussions after the recent presidential election revolves around the movement of the nation’s Latino voters — primarily men — from being overwhelmingly Democratic over the past 25 years to favoring Donald Trump.

Less clear is what that shift says about long term voting trends among this growing segment of the electorate: is it a genuine realignment or a reflection of the so-called “Trump effect.”

“I think Arizona will be a great example of this, as a majority of Latino men may have voted for Trump, but I guarantee you a lot of them voted for Ruben Gallego for Senate,” said Sonja Diaz, co-founder of the Latina Futures Lab at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA).

Gallego, a Democrat, defeated his Republican rival and right-wing firebrand Kari Lake to become Arizona’s first Latino US Senator.

Numbers are only part of the story

Election results say little about voter attitudes, a question better left to exit polls or election eve polls, which interview voters on or in the days and weeks prior to Election Day.

And while the raw numbers do reflect a rightward tilt among Latinos this election cycle, a deeper understanding of what drove that shift may not emerge for weeks or months as the data comes in and experts have a chance to take a deeper dive into voter files.

“All these previous polls show a shift toward Republicans when actually, it was a shift toward Trump,” explains Rodrigo Dominguez-Villegas, co-director of research at UCLA’s Latino Public Policy Institute. “What’s different is the size of that shift.”

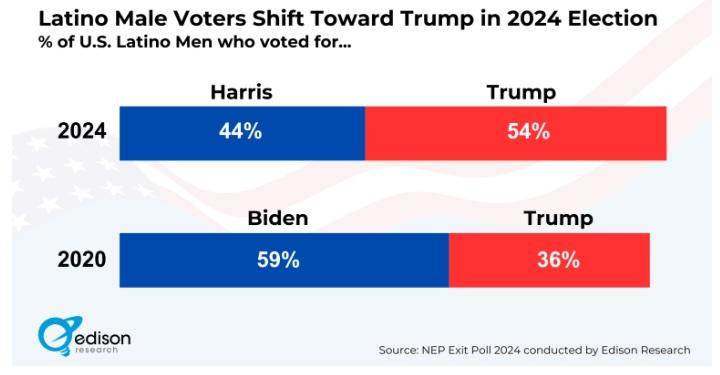

The Edison poll used by most media outlets showed Latino support at 52 percent for Democrat Kamala Harris and 45 percent for Trump and that Latino men voted overwhelmingly for Trump over Harris, 55 percent to 43 percent. Latino women remained in the Democrat’s column, with 60 percent vs. 38 percent for Trump. A Washington Post exit poll showed similar results.

Four years ago, the Edison poll found that Latinos voted 65 percent for Biden and 32 percent for Trump, reflecting a 13-point decline for Democrats in 2024.

But a poll conducted in the weeks before the election, sponsored by a slate of progressive groups and involving a large number of Latino voters, found a much smaller margin of support for Trump among Latino respondents, at just 37 percent vs. 62 percent for Harris.

This poll found that no majority of Latino men favored Trump; only 40 percent, which is up from 2020, but not a majority.

“Because of all this, it’s important not to draw big conclusions yet,” Dominguez-Villegas said.

Other experts question the conclusions drawn from exit polls.

Nancy Lopez, a professor of sociology and criminology at the University of New Mexico, believes it is a serious problem to lump all Latinos together, given the dearth of in-depth analysis about their race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

“If we had that data, we would probably find that the movement towards Trump did not happen the same way among all Latinos and that Afro-Latinos probably voted like African Americans,” said Lopez, who is Afro-Latino and Dominican and was born in New York.

Emerging theories

While social media is rife with largely anecdotal explanations about what drove the “Latino turn” toward Trump, researchers say polling reveals a few key indicators, with the economy topping the list.

“The inflation issue is important; it comes up in many polls,” Dominguez-Villegas explained, adding that a longer-term shift among working-class voters—starting with whites and now drawing in more voters of color—toward Trump’s populist message also helped fuel his decisive election win.

“The Democratic party has lost its ability to resonate with most Americans,” explained Sonja Diaz. “And that includes people of color.”

Diaz mentioned that despite a seemingly strong economy, inequality between demographic groups continues to expand. Inflation does the rest.

Donald Trump also expressly invited “Hispanics or Latinos” into his campaign and made culturally competent commercials in Spanish, reinforcing the economic message of this election, which resonated with those lower down on the economic ladder. The inherent “machismo” and misogyny that defines much of the Trump persona might also have held a certain appeal to some segment of Latino men.

Good vs. bad immigrant

Finally, there is one other possible explanation for why so many Latinos swung toward a candidate whose campaign and entire political career has been built on attacking immigrants: the desire to belong.

Research by Efren Perez, a professor of political science and psychology at UCLA, reveals that Latinos who prioritize their American identity over their ethnic identity tend to see Trump’s attacks on immigrants and other minorities as something that does not directly concern them. Some may even sympathize with Trump’s rhetoric.

It’s the “good immigrant vs. bad immigrant” psychology.

“Some Latinos cling to anti-immigrant sentiments out of a deep desire to assimilate into the culture in which they live,” Dominguez Villegas said.

Journalist Paola Ramos, in her book Defectors, speaks of a similar phenomenon: a growing group of Latino voters who find solace in the authoritarian characteristics of a leader because they know this style from their past or for other reasons.

For Nancy Lopez of the University of New Mexico, “the identity narrative put forward by the Republican campaign was more appealing to people who do not see their future linked to the population that has been most oppressed.”