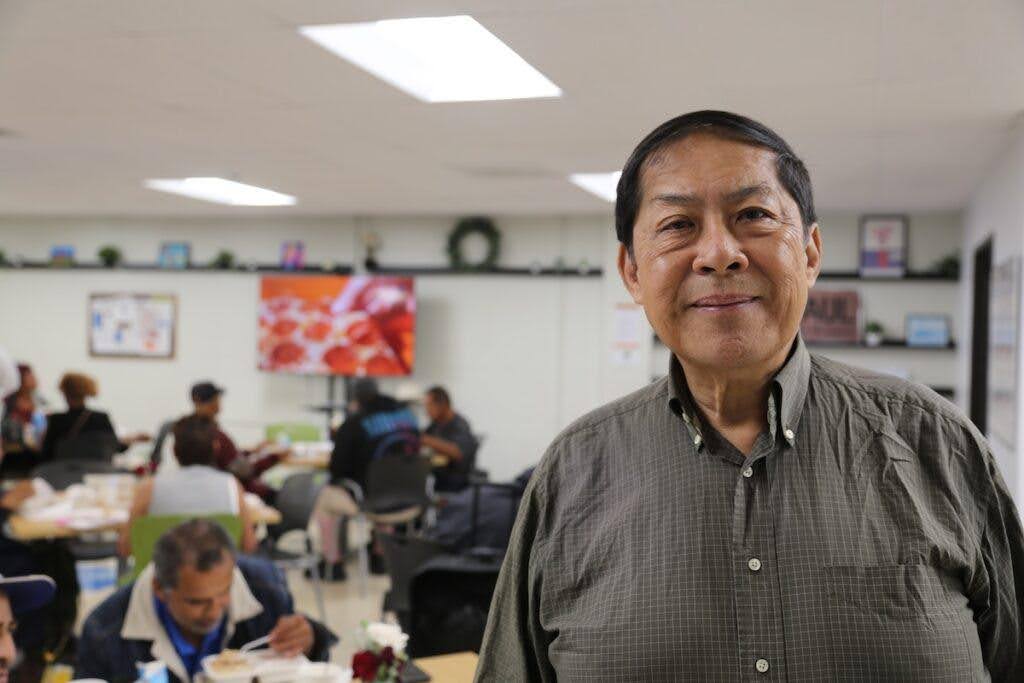

LOS ANGELES – It’s a warm Tuesday as a line forms outside Casa Milagrosa, a day center for the unhoused on the edge of Korea Town. Among the crowd is Wilki Tom, a 68-year-old Los Angeles native who for the past two years has received regular medical checks here.

For Tom and many others, these “street medicine” services are a lifeline, and thanks to recent changes to Medi-Cal they are now financially viable over the long term.

“The nurses know me here. It’s been the same regular doctor for most of the year,” says Tom, who compares that to past experiences with his primary care physicians who “rotate in and out,” often mixing up his first and last name.

“It’s 3 to 4 months before I can see my primary,” he notes. “I waited three years to get eye surgery. I had cataract surgery. It’s like, a new doctor comes in… this is the third primary physician I’ve had in two years, and the new one doesn’t know what the previous one was doing.”

He adds, “The folks here know my name. They see me every week. They’re consciously aware of my situation.” And that, in turn, has forced him to take better care of himself. “It keeps you on your toes,” he says. “You have expectations for yourself.”

That level of connection between provider and patient is a key hallmark of the street medicine model, which seeks to take health care out of the hospital and bring it to where the people are who need it most. In this case, the more than 75,000 individuals across LA County who are without shelter or unstably housed, according to the 2024 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count.

For many of these people, having regular and reliable access to health care has been as elusive as finding affordable housing.

That may be starting to shift, however, following a series of important changes at the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) – which oversees Medi-Cal – that now allow street medicine providers to bill directly for the services they render outside a hospital setting, which is most of the time.

Brian Zunner-Keating with UCLA’s Health and Homeless Care Collaborative says this is “something that is unheard of historically.”

Street medicine providers have traditionally relied on philanthropy, an unstable and unpredictable funding model. Any medical services, moreover, needed to be delivered within a licensed health care facility to be billed to Medi-Cal. The new DHCS guidelines have upended that old paradigm, allowing groups like Zunner-Keating’s to continue with and even expand their work.

“We are really grateful to have that sustainable way to continue our program,” he notes of the recent changes.

UCLA manages five teams across much of LA County, from the San Fernando Valley to the downtown metro area, South LA and the city’s West Side. According to DHCS, there are around 25 such programs statewide.

Zunner-Keating’s team, which visits Casa Milagrosa once a week, currently includes a physician, a nurse and a community health worker, with plans in place to add two part-time social workers and two part-time psychiatrists.

That expansion of mental health services, as well as housing navigation and a range of other supports, form part of what’s known as Enhanced Care Management (ECM), a new Medi-Cal benefit that covers a range of care, both clinical and non-clinical.

For staff at Casa Milagrosa, a communal sanctuary for some of LA’s most downtrodden, it means they’re now able to bill Medi-Cal for these services. “It has definitely impacted our guests,” says Program Manager Veronica Garcia.

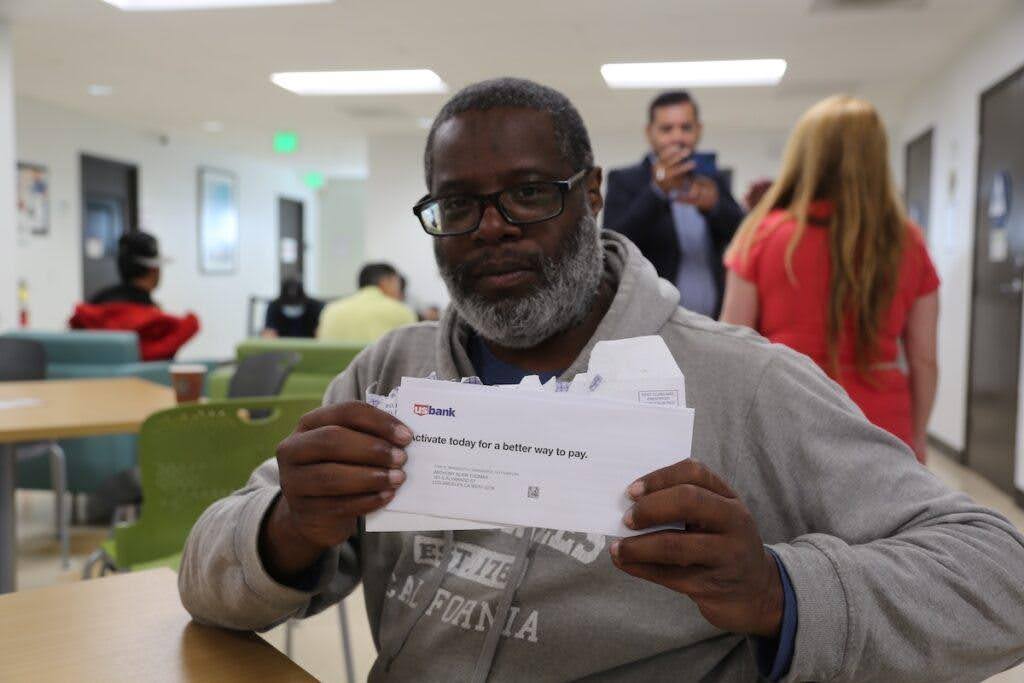

One of those guests is Anthony, a regular at Casa Milagrosa. Born in the Bay Area, he’s spent most of his adult life in Los Angeles.

“The city took my car because I hadn’t renewed registration,” he says. “I tried to get it back, but the bank wanted me to make all the back payments and payments to the tow yard. I didn’t have the money, so I had to let it go. So basically, I have nothing.”

Working with case managers at Casa Milagrosa, Anthony was able to secure a new ID, which he needed to open a bank account. “I’ve been slowly rebuilding my life, such as it was. And I thought it was important to get that foundation.”

Under the new DHCS guidelines, Casa Milgrosa can now be paid through Medi-Cal for these services.

“I really saw a need to merge some of that social support with the medical care,” says Iliana Ramirez, who runs ECM services as part of Zunner-Keating’s team and spent years as a social worker focused on housing in her prior role. “A lot of the folks, even after they were housed, still had a lot of health problems. Still had a lot of fear of being connected to a medical team.”

She says the newly expanded services have “allowed for providers to take the time to spend with a patient” and that being able to “connect with them as a human goes a long way.”

Outside, Tom gets his blood pressure taken, the rapport he shares with his provider evident as they exchange pleasantries. “It feels great,” he says. “Even if there is nothing wrong, I will stop to say good morning and hi.”

Zunner-Keating echoes Ramirez. “We’re able to go that extra mile,” adding that with the Medi-Cal expansion has come a “boom in street medicine teams, which we are so excited about because the need is so vast in LA County. And it has been unmet for years.”