AAPI young adults who are queer or trans often find themselves alone: estranged from traditional families and friends who are not supportive or don’t understand their identity.

“We don’t often think of caregiving as something that we need for ourselves. We think caregiving is individual, in a home, or there’s someone that’s giving care to their elder parent,” said Dianara Rivera, Director of Narrative Strategy at the Asian American Resource Workshop. “But caregiving is political. We’ve seen the legislative and political attacks on the queer community. We have to find ways to take care of ourselves and to take care of each other,” Rivera told EMS.

“When we bring caregiving into the public space and make it communal, we really learn a lot. There’s few and far between spaces for our community,” she said.

Narrative change

Rivera grew up in Jacksonville, Florida. “I felt pretty isolated. We were not the only Filipino family but we were definitely one of the few. I had my Filipino friends, but honestly, back then I didn’t even know I was queer. I did not figure it out till I was 20.”

“And I did not see a way I was supposed to be, especially as a queer person, even though I didn’t know it yet. So, I really had to figure it out on my own,” she said.

Based in Boston, Massachusetts, AARW is one of five organizations involved with Asian Americans Advancing Justice-AAJC’s Narrative Change and Caregiving Project, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Through the initiative, AARW aimed to collect stories and art about what interdependence looks like in queer and trans communities. The work is being shared with the public and policymakers.

Not your model minority

AARW’s project also aims to combat the model minority myth. While some of the organization’s previous initiatives have focused on AAPI elderly people, this project engaged solely young queer and trans adults.

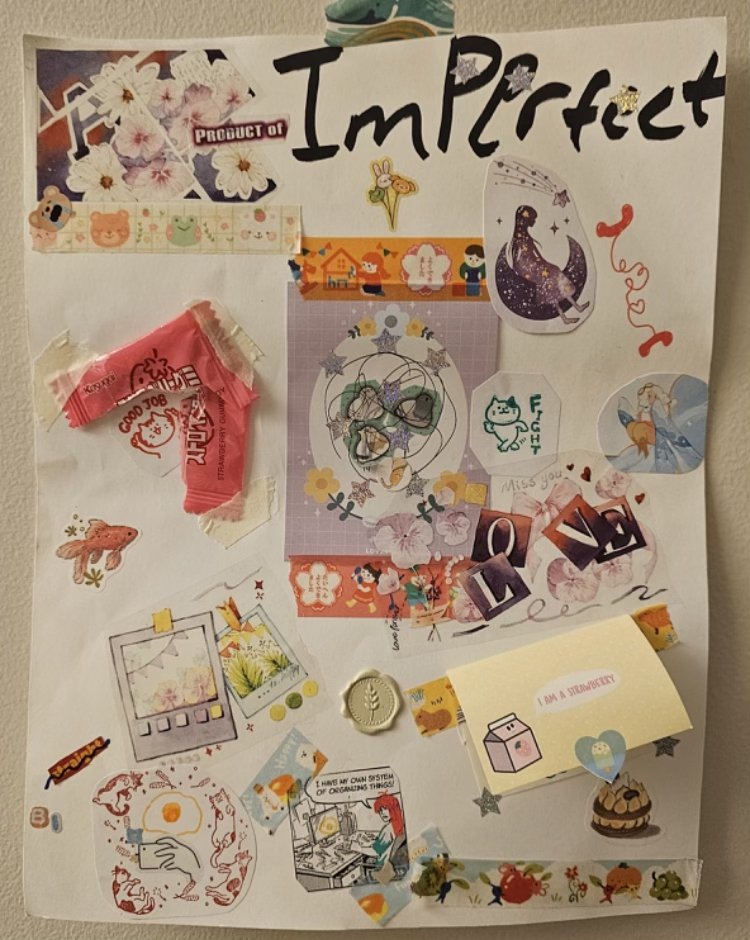

The organization created a series of workshops for the local QTAPI community to write, paint, and draw.

“There’s a lot of expectations for us to fit the model minority and stay submissive to the American gaze, but I say be brash, loud, and unapologetic. Disrupt the norm of white cisnormative America,” wrote Jenny Ly, who also created a mosaic of found objects at the first workshop last August.The complexity of identity

“At AARW, I’ve met a lot of lovely queer folks at events that make me realize that we need more intersecting identity spaces to care and love for each other. Being QTAPI is complex, but to embrace my vulnerability is being able to accept myself and the new things I discover about being QTAPI,” wrote Ly. A poetry writing workshop was also held that month.

Last September, AARW facilitated an “Ask for Help, Ask for Love,” workshop, aiming to challenge the myth within the AAPI community that asking for help is shameful and burdensome to the person who is asked. Participants explored the barriers which made them fearful of asking for help, including: fear of rejection, past rejections, and the myth that one must be strong amid a community that is struggling.

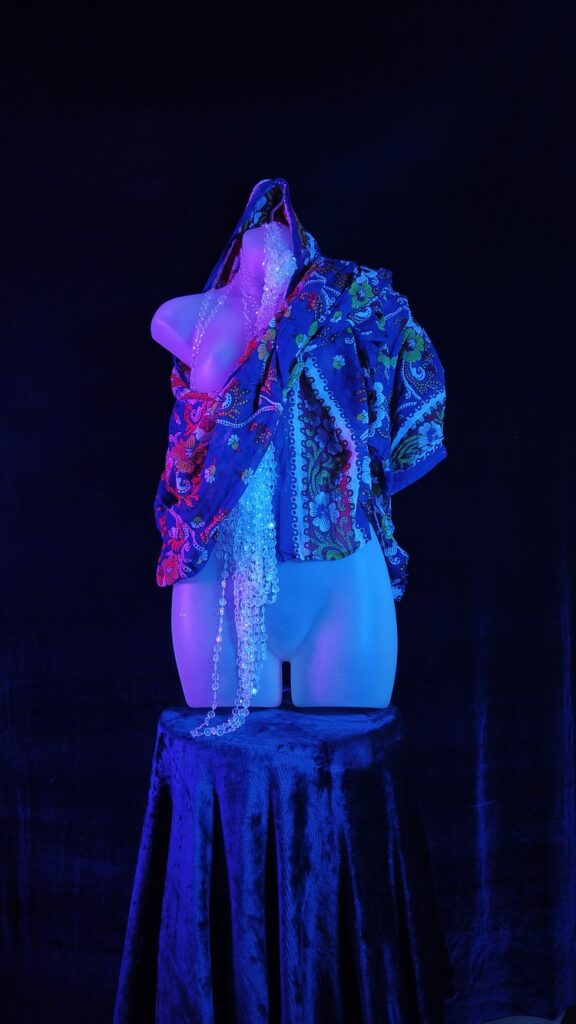

A grandmother’s sari

The final workshop in December featured photography. One person brought a photo of a fragment of a sari. “My grandmother passed away when she was very young. When my mother came to America, the only thing she had of her mother’s was this sari. Today, it’s the only thing left of my grandmother,” they wrote.

“My mother gave me a piece of the sari, which I wear as a scarf on special occasions, and she kept the other half. Photographing this scarf feels like immortalizing my grandmother’s memory,” wrote the photographer.

“I was really happy to be able to give a lot of folks an opportunity to be able to share their knowledge and practices of caregiving with the larger community,” said Rivera. “The feedback I got was really that it was great to have this space specifically for the QTAPI community. Being able to just bring the sense of aliveness was really heartwarming.”